The northern and southern poles change places. What will this lead to?

-

Dec, Sat, 2024

- 0

- 145 views

- 21 minutes Read

By Alan Buis,

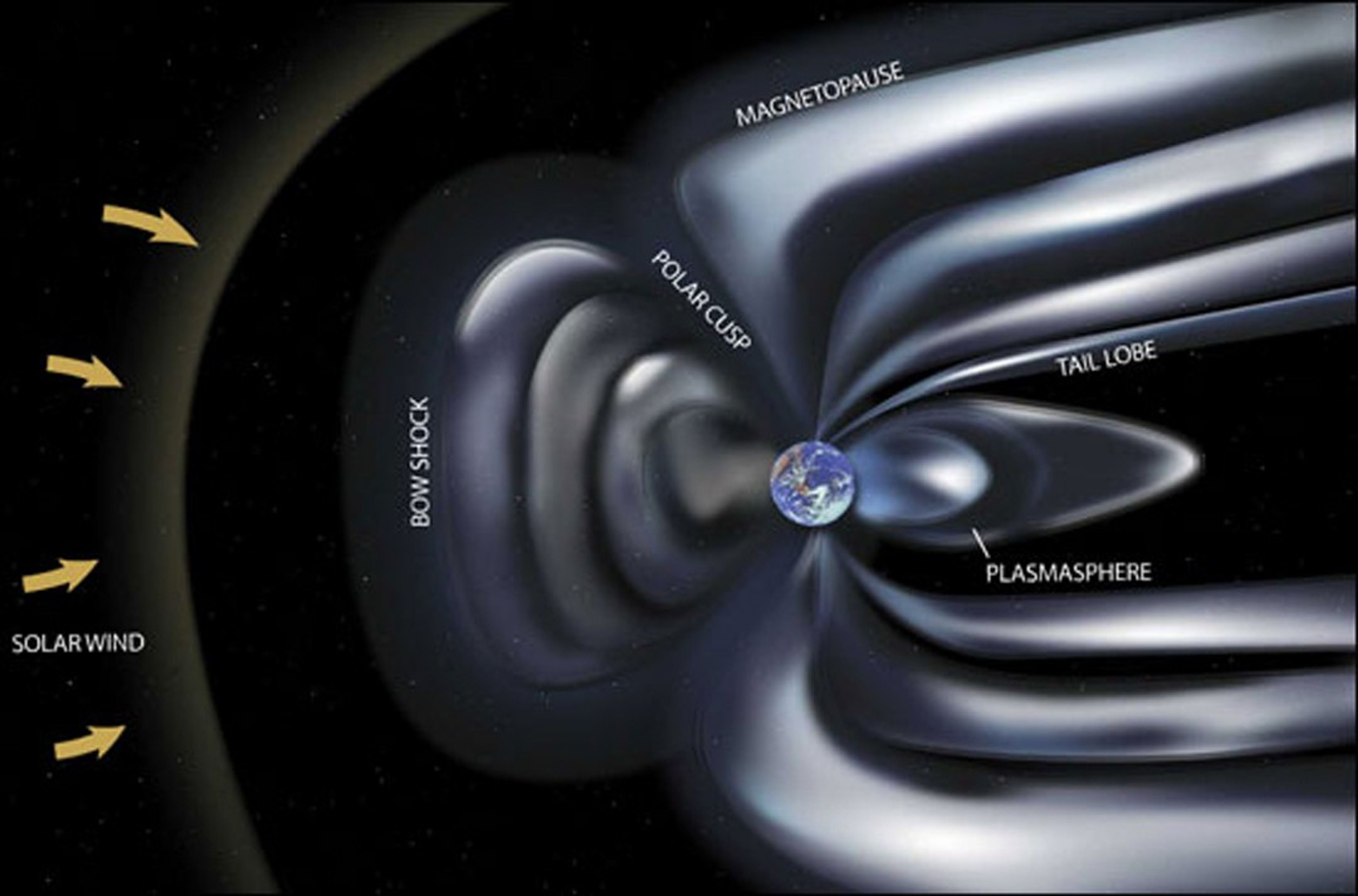

Earth is surrounded by an immense magnetic field, called the magnetosphere. Generated by powerful, dynamic forces at the center of our world, our magnetosphere shields us from erosion of our atmosphere by the solar wind, particle radiation from coronal mass ejections (eruptions of large clouds of energetic, magnetized plasma from the Sun’s corona into space), and from cosmic rays from deep space. Our magnetosphere plays the role of gatekeeper, repelling these forms of energy that are harmful to life, trapping most of it safely away from Earth’s surface. You can learn more about Earth’s magnetosphere here.

Since the forces that generate our magnetic field are constantly changing, the field itself is also in continual flux, its strength waxing and waning over time. This causes the location of Earth’s magnetic north and south poles to gradually shift, and to even completely flip locations every 300,000 years or so. That might be somewhat important if you use a compass, or for certain animals like birds, fish and sea turtles, whose internal compasses use the magnetic field to navigate.

Some people have claimed that variations in Earth’s magnetic field are contributing to current global warming and can cause catastrophic climate change. However, the science doesn’t support that argument. In this blog, we’ll examine a number of proposed hypotheses regarding the effects of changes in Earth’s magnetic field on climate. We’ll also discuss physics-based reasons why changes in the magnetic field can’t impact climate.

Launched in November 2013 by the European Space Agency (ESA), the three-satellite Swarm constellation is providing new insights into the workings of Earth’s global magnetic field. Generated by the motion of molten iron in Earth’s core, the magnetic field protects our planet from cosmic radiation and from the charged particles emitted by our Sun. It also provides the basis for navigation with a compass.

Based on data from Swarm, the top image shows the average strength of Earth’s magnetic field at the surface (measured in nanotesla) between January 1 and June 30, 2014. The second image shows changes in that field over the same period. Though the colors in the second image are just as bright as the first, note that the greatest changes were plus or minus 100 nanotesla in a field that reaches 60,000 nanotesla.

Hypotheses:

1. Shifts in Magnetic Pole Locations

The position of Earth’s magnetic north pole was first precisely located in 1831. Since then, it’s gradually drifted north-northwest by more than 600 miles (1,100 kilometers), and its forward speed has increased from about 10 miles (16 kilometers) per year to about 34 miles (55 kilometers) per year. This gradual shift impacts navigation and must be regularly accounted for. However, there is little scientific evidence of any significant links between Earth’s drifting magnetic poles and climate.

2. Magnetic Pole Reversals

During a pole reversal, Earth’s magnetic north and south poles swap locations. While that may sound like a big deal, pole reversals are common in Earth’s geologic history. Paleomagnetic records tell us Earth’s magnetic poles have reversed 183 times in the last 83 million years, and at least several hundred times in the past 160 million years. The time intervals between reversals have fluctuated widely, but average about 300,000 years, with the last one taking place about 780,000 years ago.

During a pole reversal, the magnetic field weakens, but it doesn’t completely disappear. The magnetosphere, together with Earth’s atmosphere, continue protecting Earth from cosmic rays and charged solar particles, though there may be a small amount of particulate radiation that makes it down to Earth’s surface. The magnetic field becomes jumbled, and multiple magnetic poles can emerge in unexpected places.

No one knows exactly when the next pole reversal may occur, but scientists know they don’t happen overnight: they take place over hundreds to thousands of years.

In the past 200 years, Earth’s magnetic field has weakened about nine percent on a global average. Some people cite this as “evidence” a pole reversal is imminent, but scientists have no reason to believe so. In fact, paleomagnetic studies show the field is about as strong as it’s been in the past 100,000 years, and is twice as intense as its million-year average. While some scientists estimate the field’s strength might completely decay in about 1,300 years, the current weakening could stop at any time.

Plant and animal fossils from the period of the last major pole reversal don’t show any big changes. Deep ocean sediment samples indicate glacial activity was stable. In fact, geologic and fossil records from previous reversals show nothing remarkable, such as doomsday events or major extinctions.

3. Geomagnetic Excursions

Recently, there have been questions and discussion about “geomagnetic excursions:” shorter-lived but significant changes in the magnetic field’s intensity that last from a few centuries to a few tens of thousands of years. During the last major excursion, called the Laschamps event, radiocarbon evidence shows that about 41,500 years ago, the magnetic field weakened significantly and the poles reversed, only to flip back again about 500 years later.

While there is some evidence of regional climate changes during the Laschamps event timeframe, ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland don’t show any major changes. Moreover, when viewed within the context of climate variability during the last ice age, any changes in climate observed at Earth’s surface were subtle.

Bottom line: There’s no evidence that Earth’s climate has been significantly impacted by the last three magnetic field excursions, nor by any excursion event within at least the last 2.8 million years.

Physical Principles

1. Insufficient Energy in Earth’s Upper Atmosphere

Electromagnetic currents exist within Earth’s upper atmosphere. But the energy driving the climate system in the upper atmosphere is, on global average, a minute fraction of the energy that drives the climate system at Earth’s surface. Its magnitude is typically less than one to a few milliwatts per square meter. To put that into context, the energy budget at Earth’s surface is about 250 to 300 watts per square meter. In the long run, the energy that governs Earth’s upper atmosphere is about 100,000 times less than the amount of energy driving the climate system at Earth’s surface. There is simply not enough energy aloft to have an influence on climate down where we live.

2. Air Isn’t Ferrous

Finally, changes and shifts in Earth’s magnetic field polarity don’t impact weather and climate for a fundamental reason: air isn’t ferrous.

Ferrous? Say what?? Bueller? Bueller?

Ferrous means “containing or consisting of iron.” While iron in volcanic ash is transported in the atmosphere, and small quantities of iron and iron compounds generated by human activities are a source of air pollution in some urban areas, iron isn’t a significant component of Earth’s atmosphere. There’s no known physical mechanism capable of connecting weather conditions at Earth’s surface with electromagnetic currents in space.

Thermal and compositional structure of the atmosphere. The upper atmosphere, comprising the mesosphere, thermosphere, and embedded ionosphere, absorbs all incident solar radiation at wavelengths less than 200 nanometers (nm). Most of that absorbed radiation is ultimately returned to space via infrared emissionsfrom carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitric oxide (NO) molecules. The stratospheric ozone layer absorbs radiation between 200 and 300 nm.

The plot on the left shows the typical global-average thermal structure of the atmosphere when the flux of solar radiation is at the minimum and maximum values of its 11-year cycle. The plot on the right shows the density of nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), and atomic oxygen (O), the three major neutral species in the upper atmosphere, along with the free electron (e−) density, which is equal to the combined density of the various ion species. The F, E, and D regions of the ionosphere are also indicated, as is the troposphere, the atmosphere’s lowest region.

Solar storms and their electromagnetic interactions only impact Earth’s ionosphere, which extends from the lowest edge of the mesosphere (about 31 miles or 50 kilometers above Earth’s surface) to space, around 600 miles (965 kilometers) above the surface. They have no impact on Earth’s troposphere or lower stratosphere, where Earth’s surface weather, and subsequently its climate, originate.

In short, when it comes to climate, variations in Earth’s magnetic field are nothing to get charged up about.

Related Feature

Earth’s Magnetosphere: Protecting Our Planet from Harmful Space Energy

By Alan Buis,

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Among the four rocky planets in our solar system, you could say that Earth’s “magnetic” personality is the envy of her interplanetary neighbors.

Unlike Mercury, Venus, and Mars, Earth is surrounded by an immense magnetic field called the magnetosphere. Generated by powerful, dynamic forces at the center of our world, our magnetosphere shields us from erosion of our atmosphere by the solar wind (charged particles our Sun continually spews at us), erosion and particle radiation from coronal mass ejections (massive clouds of energetic and magnetized solar plasma and radiation), and cosmic rays from deep space. Our magnetosphere plays the role of gatekeeper, repelling this unwanted energy that’s harmful to life on Earth, trapping most of it a safe distance from Earth’s surface in twin doughnut-shaped zones called the Van Allen Belts.

But Earth’s magnetosphere isn’t a perfect defense. Solar wind variations can disturb it, leading to “space weather” — geomagnetic storms that can penetrate our atmosphere, threatening spacecraft and astronauts, disrupting navigation systems and wreaking havoc on power grids. On the positive side, these storms also produce Earth’s spectacular aurora. The solar wind creates temporary cracks in the shield, allowing some energy to penetrate down to Earth’s surface daily. Since these intrusions are brief, however, they don’t cause significant issues.

Because the forces that generate Earth’s magnetic field are constantly changing, the field itself is also in continual flux, its strength waxing and waning over time. This causes the location of Earth’s magnetic north and south poles to gradually shift and to completely flip locations about every 300,000 years or so. You can learn why magnetic field polarity changes and shifts have no effect on climate on the timescales of human lifetimes and aren’t responsible for Earth’s recent observed warming here.

Launched in November 2013 by the European Space Agency (ESA), the three-satellite Swarm constellation is providing new insights into the workings of Earth’s global magnetic field. Generated by the motion of molten iron in Earth’s core, the magnetic field protects our planet from cosmic radiation and from the charged particles emitted by our Sun. It also provides the basis for navigation with a compass.

Based on data from Swarm, the top image shows the average strength of Earth’s magnetic field at the surface (measured in nanotesla) between January 1 and June 30, 2014. The second image shows changes in that field over the same period. Though the colors in the second image are just as bright as the first, note that the greatest changes were plus or minus 100 nanotesla in a field that reaches 60,000 nanotesla.

To understand the forces that drive Earth’s magnetic field, it helps to first peel back the four main layers of Earth’s “onion” (the solid Earth):

- The crust, where we live, which is about 19 miles (31 kilometers) deep on average on land and about 3 miles (5 kilometers) deep at the ocean bottom.

- The mantle, a hot, viscous mix of molten rock about 1,800 miles (2,900 kilometers) thick.

- The outer core, about 1,400 miles (2,250 kilometers) thick and composed of molten iron and nickel.

- The inner core, a roughly 759-mile-thick (1,221-kilometer-thick) solid sphere of iron and nickel metals about as hot as the Sun’s surface.

Nearly all of Earth’s geomagnetic field originates in the fluid outer core. Like boiling water on a stove, convective forces (which move heat from one place to another, usually through air or water) constantly churn the molten metals, which also swirl in whirlpools driven by Earth’s rotation. As this roiling mass of metal moves around, it generates electrical currents hundreds of miles wide and flowing at thousands of miles per hour as Earth rotates. This mechanism, which is responsible for maintaining Earth’s magnetic field, is known as the geodynamo.

At Earth’s surface, the magnetic field forms two poles (a dipole). The north and south magnetic poles have opposite positive and negative polarities, like a bar magnet. The invisible lines of the magnetic field travel in a closed, continuous loop, flowing into Earth at the north magnetic pole and out at the south magnetic pole. The solar wind compresses the field’s shape on Earth’s Sun-facing side, and stretches it into a long tail on the night-facing side.

The study of Earth’s past magnetism is called paleomagnetism. Direct observations of the magnetic field extend back just a few centuries, so scientists rely on indirect evidence. Magnetic minerals in ancient undisturbed volcanic and sedimentary rocks, lake and marine sediments, lava flows and archeological artifacts can reveal the magnetic field’s strength and directions, when magnetic pole reversals occurred, and more. By studying global evidence and data from satellites and geomagnetic observatories and analyzing the magnetic field’s evolution using computer models, scientists can construct a history of how the field has changed over geologic time.

NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

Earth’s mid-ocean ridges, where tectonic plates form, provide paleomagnetists with data stretching back about 160 million years. As lava continually erupts from the ridges, it spreads out and cools, and the iron-rich minerals in it align with the geomagnetic field, pointing north. Once the lava cools to about 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit (700 degrees Celsius), the strength and direction of the magnetic field at that time become “frozen” into the rock. By sampling and radiometrically dating the rock, this record of the magnetic field can be revealed.

Studies of Earth’s magnetic field have revealed much of its history.

For example, we know that over the past 200 years, the magnetic field has weakened about 9 percent on a global average. However, paleomagnetic studies show the field is actually about the strongest it’s been in the past 100,000 years, and is twice as intense as its million-year average.

We also know there’s a well-known “weak spot” in the magnetosphere that is present year-round. Located over South America and the southern Atlantic Ocean, the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) is an area where the solar wind penetrates closer to Earth’s surface. It’s created by the combined influences of the geodynamo and the tilt of Earth’s magnetic axis. While charged solar particles and cosmic ray particles within the SAA can fry spacecraft electronics, they don’t affect life on Earth’s surface.

We know the positions of Earth’s magnetic poles are continually moving. Since it was first precisely located by British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer Sir James Clark Ross in 1831, the magnetic north pole’s position has gradually drifted north-northwest by more than 600 miles (1,100 kilometers), and its forward speed has increased, from about 10 miles (16 kilometers) per year to about 34 miles (55 kilometers) per year.

NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

Earth’s magnetic poles are not the same as its geodetic poles, which most people are more familiar with. The locations of Earth’s geodetic poles are determined by the rotational axis our planet spins upon. That axis doesn’t spin evenly, like a globe on your desk. Instead, it wobbles slightly. This causes the position of the true north pole to shift slightly over time. Numerous processes on Earth’s surface and within its interior contribute to this wander, but it’s primarily due to the movement of water around Earth. Since observations began, the position of Earth’s rotational axis has drifted toward North America by about 37 feet (12 meters), though never more than about 7 inches (17 centimeters) in a year. These wobbles don’t affect our daily life, but they must be considered to get accurate results from global navigation satellite systems, Earth-observing satellites and ground observatories. The wobbles can tell scientists about past climate conditions, but they’re a consequence of changes in continental water storage and ice sheets over time, not a cause of them.

By far the most dramatic changes impacting Earth’s magnetosphere are pole reversals. During a pole reversal, Earth’s magnetic north and south poles swap locations. While that may sound like a big deal, pole reversals are actually common in Earth’s geologic history. Paleomagnetic records, including those revealing variations in magnetic field strength, tell us Earth’s magnetic poles have reversed 183 times in the last 83 million years, and at least several hundred times in the past 160 million years. The time intervals between reversals have fluctuated widely, but average about 300,000 years, with the last taking place about 780,000 years ago. Scientists don’t know what drives pole reversal frequency, but it may be due to convection processes in Earth’s mantle.

During a pole reversal, the magnetic field weakens, but it doesn’t completely disappear. The magnetosphere, together with Earth’s atmosphere, still continue to protect our planet from cosmic rays and charged solar particles, though there may be a small amount of particulate radiation that makes it down to Earth’s surface. The magnetic field becomes jumbled, and multiple magnetic poles can emerge at unexpected latitudes.

No one knows exactly when the next pole reversal may occur, but scientists know they don’t happen overnight. Instead, they take place over hundreds to thousands of years. Scientists have no reason to believe a flip is imminent.

Finally, there are “geomagnetic excursions:” shorter-lived but significant changes to the intensity of the magnetic field that last from a few centuries to a few tens of thousands of years. Excursions happen about 10 times as frequently as pole reversals. An excursion can re-orient Earth’s magnetic poles as much as 45 degrees from their previous position, and reduce the strength of the field by up to 20 percent. Excursion events are generally regional, rather than global. There have been three significant excursions in the past 70,000 years: the Norwegian-Greenland Sea event about 64,500 years ago, the Laschamps event between 42,000 and 41,000 years ago, and the Mono Lake event about 34,500 years ago.